September 16 – 28

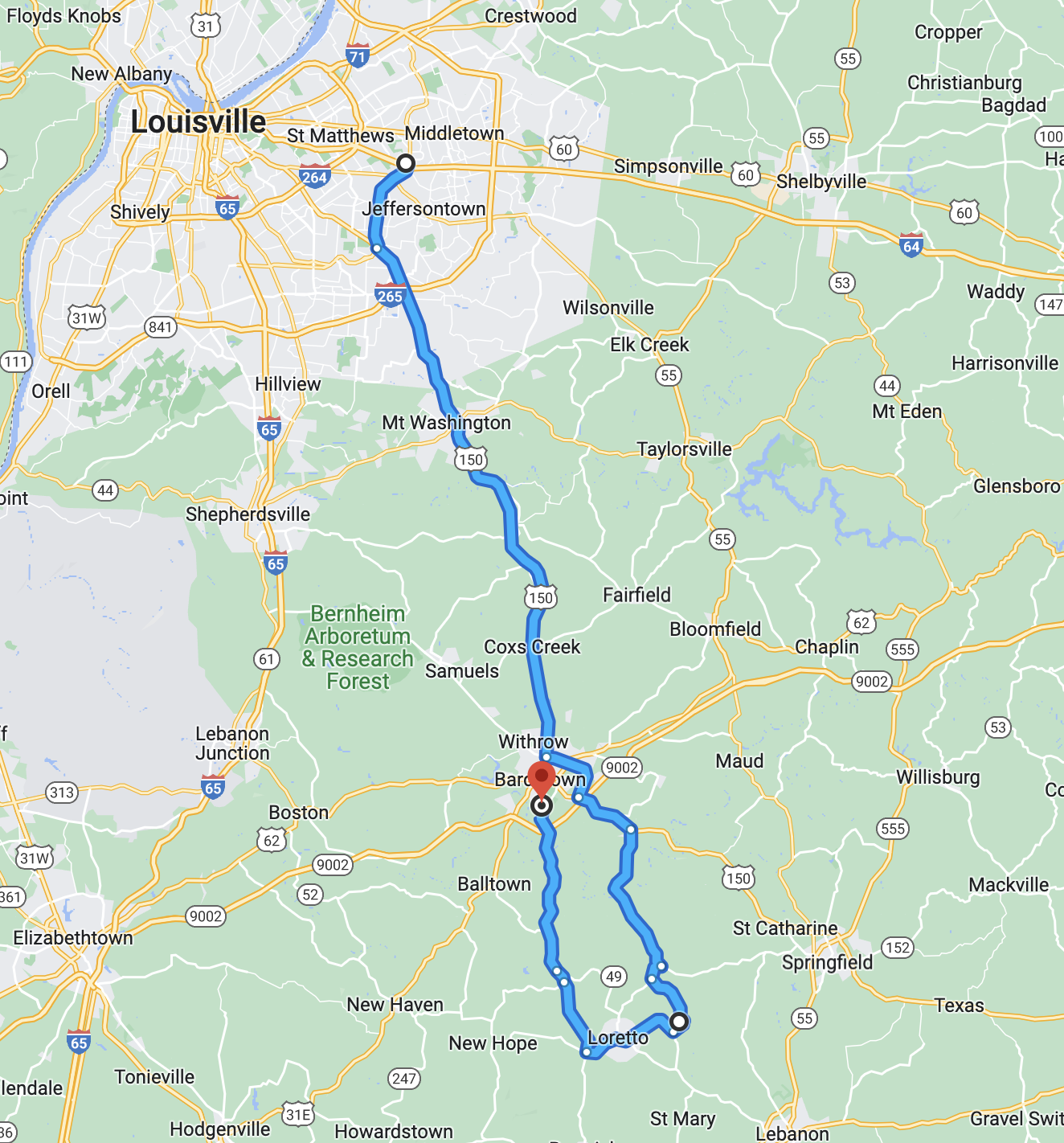

Our first full day on the Bourbon Trail would be a full one, both from a time elapsed standpoint and an enjoyment quotient perspective. We’d be heading south 50 miles to the small town of Loretto, home of Maker’s Mark. Long one of my favorite brands (I’ve also consumed prodigious quantities of Jack Daniels), their 46 ranks near the top of my list of bourbons and I always seem to have a bottle at the house.

This would be a tour and a tasting; we checked in at the reception desk and although early, contemplated getting a cocktail at the bar there, common sense finally prevailing as we confronted the fact that it was just 11am and we had a full day ahead of us.

Making whiskey is a fairly simple thing to do. First one decides what the ratio of the various grains will be, the recipe so to speak and generally, it is distilled from a fermented mash of grain, yeast and water. In Kentucky, to be called a bourbon, the “mash bill” must have a minimum of 51% corn. For most bourbons, the average is about 70% and other grains such as rye, malted barley and wheat are considered the “flavor” grain.

The first step is mashing where the sugars contained in the grain are extracted before fermentation. The grains that are being used are ground up, put in a large tank (called a mash tun or tub) with hot water, and agitated. Even if the distiller isn’t making malt whisky, some ground malted barley is typically added to help catalyze the conversion of starches to sugars. The resulting mixture resembles porridge. Once as much sugar as possible has been extracted, the mixture—now known as mash or wort (if strained of solids) moves on to the fermentation stage.

Fermentation occurs when the mash/wort meets yeast, which gobbles up all the sugars in the liquid and converts them to alcohol. This takes place in giant vats, often called washbacks. The process can take anywhere from 48 to 96 hours, with different fermentation times and yeast strains resulting in a spectrum of diverse flavors. The resulting beer-like liquid, called distiller’s beer or wash, clocks in at around 7%-10% ABV before it goes into the still for distillation.

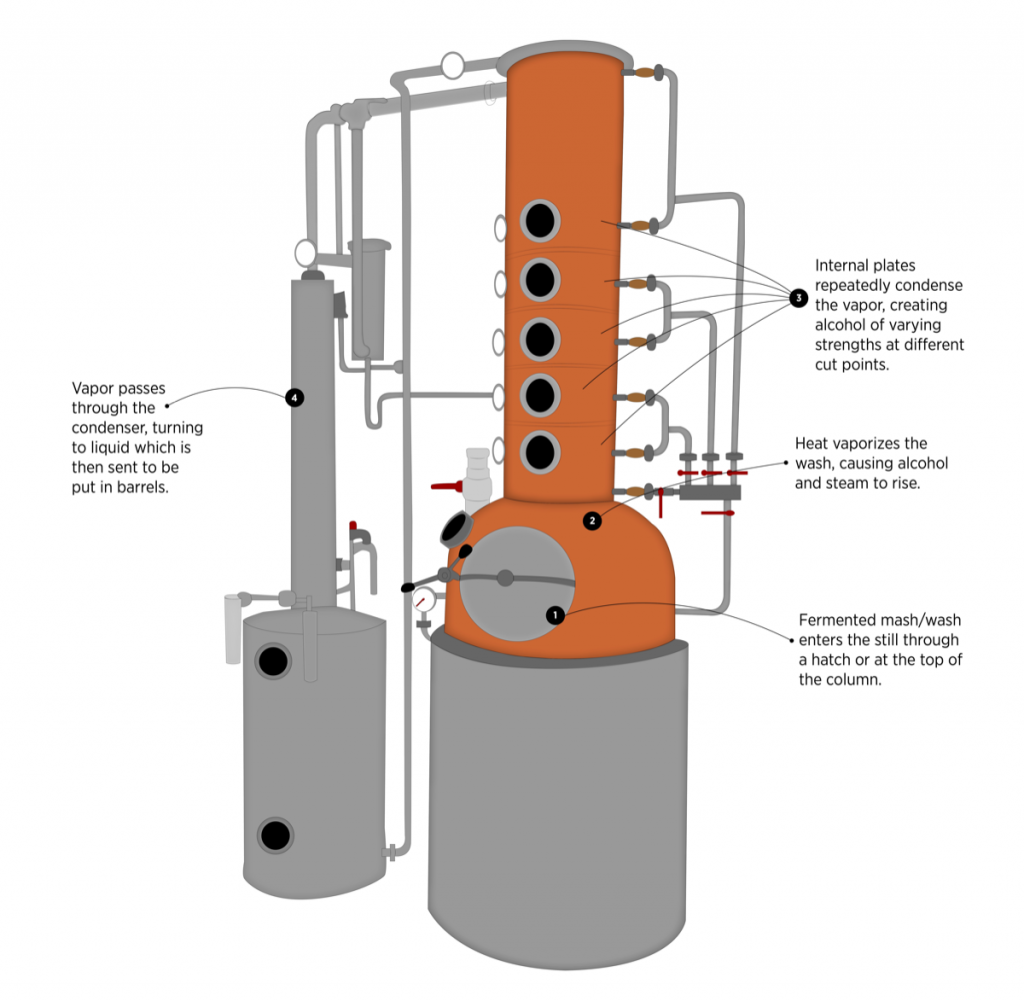

The process of distilling increases the alcohol content of the liquid and brings out volatile components, both good and bad. Stills are usually made of copper, which helps strip spirits of unwanted flavor and aroma compounds. The two most common types of stills—pot stills and column stills—function differently. Both are outlined below.

Pot stills – This form of distillation is a batch process where some styles use double-distillation and others are distilled three times. The wash goes into the first still, often called the low wines still, where it’s heated up. Alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water, so the alcohol vapors rise off the liquid and into the still neck and lyne arm, eventually reaching the condenser, which turns them to liquid once again. The resulting liquid, which is about 20% ABV, goes into the second still, or spirit still, where the process is repeated. At this time, a third distillation can occur. The resulting final spirit comes off the still starting at around 60%-70% ABV. The distiller discards or reserves a certain amount of spirit from the beginning and end of the run, known as heads and tails, due to their unwanted flavors and aromas. The rest—known as the heart—goes into barrels, often by way of a spirit safe.

Column stills – Also known as continuous or Coffey stills. These work continuously and efficiently, removing the need for the batch process of pot stills. The distiller’s beer is fed into the column still at the top and begins descending, passing through a series of perforated plates. Simultaneously, hot steam rises from the bottom of the still, interacting with the beer as it flows downward, separating out the solids and unwanted substances, and pushing up the lighter alcohol vapors. When the vapors hit each plate, they condense, which helps get rid of heavy substances like congeners and increases the alcohol content. Eventually, the vapor is directed into a condenser. Column stills can produce spirit up to 95% ABV, although most whiskies are distilled to lower proofs.

Nearly all whiskies are aged in wood—usually oak—containers. One notable exception is corn whiskey, which may be aged or unaged. Bourbon, rye, and other types of American whiskey must be aged in new charred oak barrels, while for other countries’ styles, the type of oak and its previous use are generally left up to the producer. Barrels are stored in warehouses, and as the whisky matures, some of the alcohol evaporates: This is known as the angels’ share, and it creates a distinct (and lovely) smell in the warehouse. Some whiskies, such as scotch, have a required minimum age.

Once matured, whisky is bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV. The whisky may be chill-filtered or filtered in another way to prevent it from becoming cloudy when cold water or ice is added. For most large whisky brands, a bottling run combines several barrels, anywhere from a few dozen to hundreds, from the distillery’s warehouses. When only one barrel is bottled at a time, it’s labeled as single cask or single barrel.

During our Maker’s tour, we got to see each step of this process of a brand that, while produced in an historic facility, is relatively new compared to its peers. Maker’s Mark began when T. William “Bill” Samuels Sr., purchased the “Burks’ Distillery” in 1953 with its first run was bottled in 1958 under the brand’s dipped red wax seal (U.S. trademark serial number 73526578). After the brand’s creation by Bill Samuels Sr., its production was overseen by his son Bill Samuels Jr. until 2011 when he announced his retirement as president and CEO at the age of 70. His son Rob Samuels succeeded him that year.

Now owned by Beam Suntory, the third largest distilled spirits maker in the world, Maker’s Mark is unusual in that no rye is used as part of the mash. Instead of rye it uses red winter wheat (16%), along with corn (70%) and malted barley (14%) in the mash bill. During the planning phase of Maker’s Mark, Samuels allegedly developed seven candidate mash bills for the new bourbon. As he did not have time to distill and age each one for tasting, he instead made a loaf of bread from each recipe and the one with no rye was judged the best tasting.

Maker’s Mark is aged for around six years, being bottled and marketed when the company’s tasters agree that it is ready. It is one of the few distillers to rotate the barrels from the upper to the lower levels of the aging warehouses during the aging process to even out the differences in temperature during the process. The upper floors are exposed to the greatest temperature variations during the year, so rotating the barrels ensures that the bourbon in all the barrels has the same quality and taste.

As we neared the end of the tour, we stopped for an explanation about the production of my favorite Maker’s product, it’s 46. As explained by them, “The innovative wood-stave-finishing process starts with fully matured Maker’s Mark at cask strength. We then insert 10 seared virgin French oak staves into the barrel and finish it for nine weeks in our limestone cellar. The result is Maker’s Mark 46: bolder and more complex, but without the bitterness typical of longer-aged whiskies.” The number 46 refers to the number of attempts they made to achieve the taste they preferred, that is this is the 46th version.

Just before our tasting, we entered the bottling room, a modern facility where the company’s uniquely shaped containers are filled, and they are hand dipped in that well known red wax. Unfortunately, just as we entered, the line went down and after crew members spent many minutes trying to get it started again, to no avail, we departed for our long-awaited tasting.

The tasting would follow the pattern we experienced the day before and would enjoy again later during our trek along the trail, that is a witty, knowledgeable host introducing us to four offerings from the distillery, offering information about each taste (aroma, taste, finish) as well as ways to enjoy it later. We finished our visit by spending some time in the gift shop and having had a full morning, went in search of lunch.

Links

Maker’s Mark: https://www.makersmark.com/

Discover more from 3jmann

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.